ARMO this week added support for a Vulnerability Exploitability eXchange (VEX) format for sharing information about vulnerabilities to Kubescape, an open source security posture management project for Kubernetes.

The VEX format was created for a Multistakeholder Process for Software Component Transparency led by the National Telecommunications and Information Administration (NTIA), an arm of the U.S. Department of Commerce. The NTIA and the Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency (CISA) then worked with NTIA and Chainguard to create OpenVEX, a specification and set of tools for reporting vulnerabilities in a format that can be read by machines. The Kubescape community worked with the Linux Foundation to create an instance of OpenVEX for Kubernetes environments.

ARMO CTO Ben Hirschberg said because Kubescape leverages the extended Berkeley Packet Filtering (eBPF) technology made available in the latest versions of Linux, it can now automatically create and consume software bills of materials (SBOMs) that incorporate VEX documentation. Kubescape makes use of eBPF to gain visibility into runtime environments. It retrieves Kubernetes objects from the API server and then scans them using the Rego query language created for the open source Open Policy Agent (OPA) project to invoke tools such as Grype and Trivy.

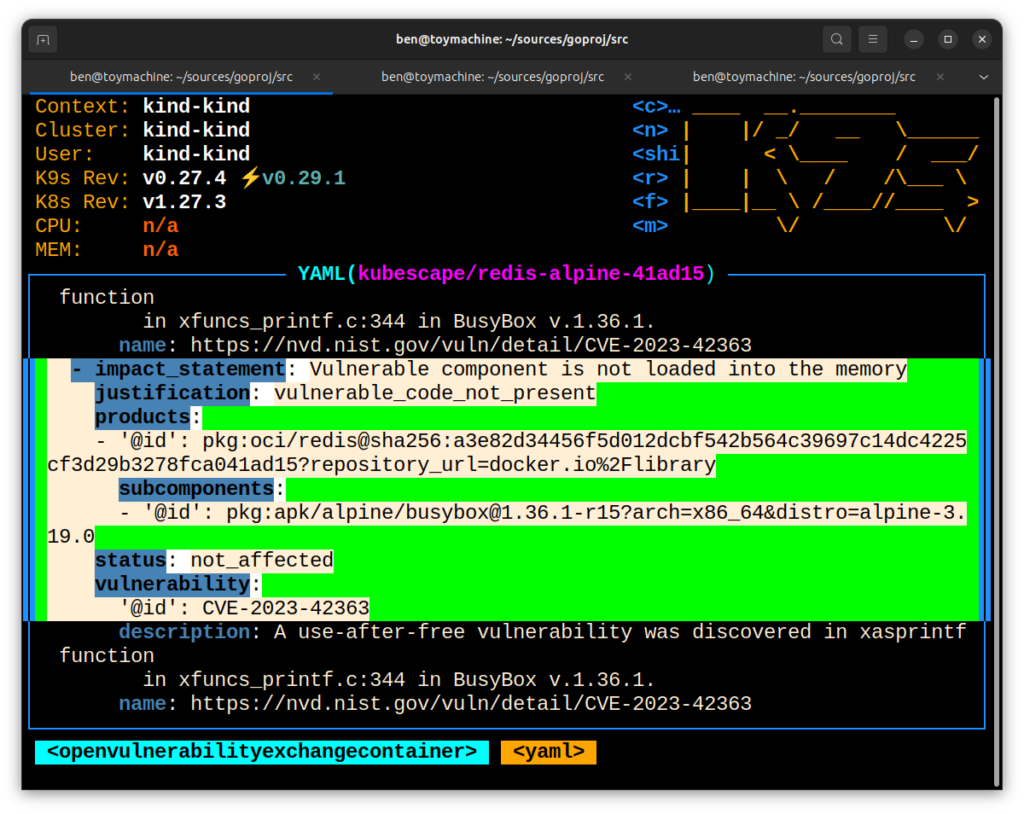

The Kubescape Operator produces VEX documents and stores them as Kubernetes API objects. These VEX documents categorize vulnerabilities as “affected” or “not affected” based on their reachability to enable IT teams to better prioritize remediation efforts.

Both Kubescape and OPA are being advanced under the auspices of the Cloud Native Computing Foundation (CNCF).

It’s not clear how many software providers have added support for VEX, but as pressure to secure software supply chains continues to mount, there is a clear need for a format that makes it simpler to share vulnerability data in a more actionable way, said Hirschberg. IT teams can now more easily determine which vulnerabilities that might exist in their IT environment can actually be exploited by cybercriminals, he noted.

Within the context of an existing DevSecOps workflow, IT teams can then programmatically remediate vulnerabilities that represent the highest level of risk to the business, said Hirschberg. Any vulnerability that can’t be reached amounts to another false-positive that, regardless of severity, only serves to make securing software more unnecessarily challenging, he added.

In the wake of an executive order issued by the Biden administration that requires federal agencies to improve software supply chain security, many enterprise IT organizations are similarly following suit. In fact, it may now only be a matter of time before more stringent regulations require organizations to revisit how they build and deploy software. The general expectation is that organizations that build and deploy software will now be required to address known vulnerabilities that, if exploited, will eventually result in fines being levied.

One way or another, the overall state of application security will improve. The only thing left to determine is how best to achieve that goal without unduly slowing down the pace at which applications can be built and deployed.